|

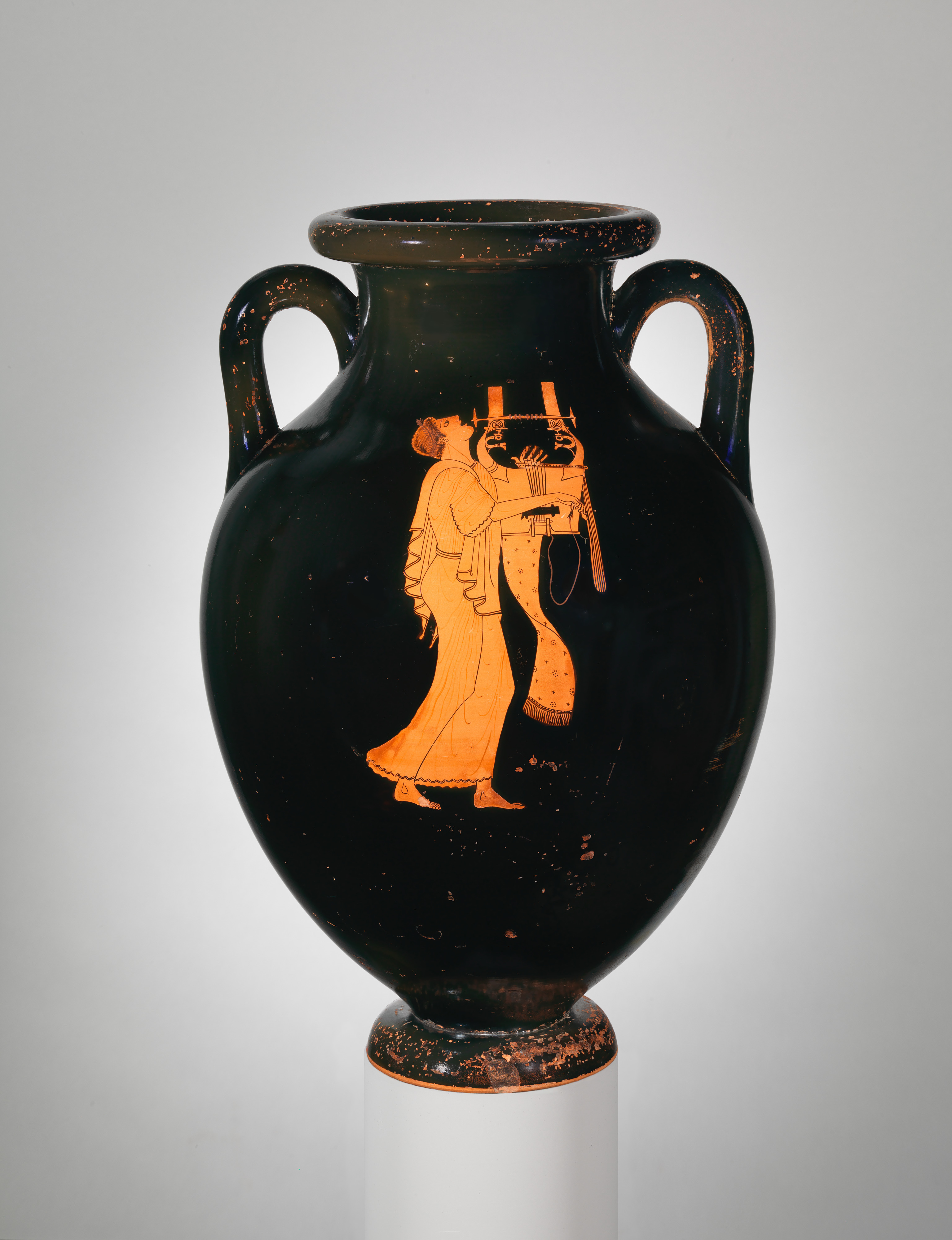

| Terracotta Amphora Attributed to the Berlin Painter Metropolitan Museum New York |

The tradition of oral epic poetry, from which rhapsodes emerged, predates written records. This tradition, represented by the "aoidoi" (bards), existed well before the 6th century BC.

An ancient Greek rhapsody was a selection of epic poetry sung by a rhapsode or rhapsodist. The word rhapsode comes from the Greek words rhapsōidēs (ῥαψῳδός), which means "stitcher of songs". This is because rhapsodes would often stitch together different passages of epic poetry to create a longer, more cohesive performance. Cleisthenes of Sicyon - Wikipedia abolished all the rhapsodes of Homer because they praised the citizens of Argos. Rhapsodes and Rhetorical Style Rhapsodes played a significant role in the performance and transmission of epic poetry in ancient Greece, with their craft closely intertwined with the development of rhetoric. The earliest incarnation of this function and role were called Aiodoi or Bards or Andres Aoidoi or Singer Men. Rhapsode was the name given to them by Plato. The difference between an Aiodo and a Rhapsode was that

Rhapsodes and Epic Poetry

Rhapsodes were professional performers of epic poetry in ancient Greece. Their name is believed to derive from the Greek word "rhaptein," meaning "to stitch," suggesting that they "stitched together" songs or poetic passages. These performers were primarily known for reciting the works of Homer and other ancient poets, including Hesiod, Archilochus, and Simonides.

Performance Style:

Rhapsodes could perform with musical accompaniment (lyre or aulos) or through declamation alone.

Their performances were often dramatic and spectacular, aimed at moving the audience emotionally.

Rhapsodic recitations became a characteristic part of the Panathenaic festivals in Athens during the 6th and 5th centuries BC.

Evolution from Aoidoi to Rhapsodes

The transition from aoidoi (earlier epic singers) to rhapsodes marks an important shift in the oral tradition of epic poetry:

Aoidoi were associated with pre-literate times and were thought to compose poems anew for each performance. Rhapsodes emerged in a more literate age and often relied on written texts to aid their performances. However, this distinction is not always clear-cut, especially through the 6th century BC.

Rhapsodes and Rhetoric

The connection between rhapsodic performance and rhetoric is multifaceted:

Formalised Systems: Scholars like Richard Enos argue that Aoidoi such as Homer and Hesiod developed formalised systems for presenting and understanding oral literature, contributing to the evolution of rhetoric as a discipline.

Performance Techniques: The dramatic nature of rhapsodic recitations, as described in Plato's "Ion," suggests a strong rhetorical component in their performances.

Commentary and Interpretation: After reciting poems, rhapsodes would often provide commentary, demonstrating analytical and persuasive skills akin to rhetoric.

Influence on Oratory: The performance techniques of rhapsodes likely influenced the development of oratorical skills in ancient Greece.

Historical Perspectives

The relationship between epic poetry, rhapsodic performance, and rhetoric has been subject to various interpretations:

Some ancient thinkers, like Plato, viewed Homeric discourse as predating formal rhetoric and considered it a non-rational approach to expression.

Others, such as Quintilian, recognised the rhetorical value in Homer's composing techniques.

Modern scholars have increasingly acknowledged the rhetorical aspects of epic poetry and its performance, seeing Rhapsodes as important figures in the development of Greek oratory and persuasive speech.

In conclusion, Rhapsodes played a crucial role in bridging the gap between epic poetry and rhetoric, embodying performance techniques that would influence the development of formal oratory in ancient Greece.

Rhapsodes

Rhapsodes were professional performers who travelled from polis to polis, reciting epic poems to audiences. They were often accompanied by music, such as the lyre or aulos. Rhapsodes were highly skilled in the art of improvisation, and they would often add their own commentary and embellishments to the poems they performed.

In preliterate societies, poetry and song served a mnemonic purpose for the memorisation and recital of the legends and folktales of those societies for storytelling which had not been written down. The rhyme and rhythm of a poem or song make the words easier to remember and pass onto others. In pre-classical Greece, oral poetry was used to relate the tales from Greek myth ─ epic tales of olden-day heroes and their interactions with the gods.

These epic tales were preserved and retold by a professional class of bards or minstrels known as aoidoi or rhapsoidoi (rhapsodes or “song-stitchers”). The craft of the rhapsodes lay in their memory and knowledge of the vast corpus of Greek myth and legend. They had the ability to select and shape episodes from this corpus for public recitation. This oral poetry was typically sung or recited in the flowing rhythm of dactylic hexameter. In general Greek poetry did not use rhyme; the Ancient Greek language had too many natural rhythms for this to be considered beautiful.

At religious festivals throughout the Athenian year. Rhapsodes, the professional performers and singers of Homeric and other epics, sought an audience at the religious events where the crowds were so gathered. As with many Greek institutions competition was important. Rhapsodes formally competed against one another before groups of judges. The winner was awarded a prize. Such competitions may have been the origins of the competitions held at the Dionysian and Lenaean festivals for tragedy and comedy theatrical performances.

It was the rhapsodes who educated the Greek masses in their mythology,

Epicharmus of Cos was a rhapsode and poet who lived in the 6th century BC.

Stesichorus of Himera was a rhapsode and poet who lived in the 7th and 6th centuries BC.

Arion of Lesbos, was a rhapsode and poet who lived in the 7th and 6th centuries BC.

Homer, the legendary author of the Iliad and the Odyssey.

It is possible to consider Thespis to have started by being an Aiodo for he travelled from place to place, performing before audiences, but the traditional story is that he was originally a choir boy who sang dithyrambs, which were songs about stories from mythology, for the public. Later he became known as the first actor and the inventor of tragedy in Ancient Greek theatre performance by stepping out of the Chorus line of the dithyrambic performance.

Rhapsodes and Ancient Greek Drama

It is very likely that Rhapsodes had a significant influence on the origin of Ancient Greek drama. Rhapsodes were professional performers of epic poetry, most famously the works of Homer like the Iliad and Odyssey. Their role in the oral tradition and public performance provided a foundation for the development of Greek theatrical practices in several ways:

Performance Techniques: Rhapsodes were skilled in recitation, often using expressive voice, gestures, and rhythm to engage audiences. These techniques likely influenced the dramatic styles employed in early Greek drama, particularly the use of actors and the chorus.

Storytelling and Myth: The content of rhapsodic performances, which centred on myths and heroic tales, formed the narrative core of much of Greek drama. Tragedies and comedies frequently drew from the same mythological corpus, reinterpreting the stories for theatrical presentations.

Choral Elements: The rhapsodic tradition also emphasised the communal and ritualistic aspects of performance. The chorus in Greek drama, which played a central role in early tragedies, might have evolved from similar collective narrative practices found in epic recitations.

Religious and Civic Context: Rhapsodic performances were often part of religious festivals, such as the Panathenaic Festival in Athens, which celebrated Athena. Similarly, Greek drama emerged in a religious context, particularly during festivals honoring Dionysus, like the City Dionysia. The overlap in ritualistic function suggests a continuity in the cultural use of performance.

Transition to Dialogue: While rhapsodes performed solo with an emphasis on narrative, Greek drama introduced dialogue between characters, often derived from interactions hinted at in epic poetry. This evolution from monologue to dialogue was a pivotal step towards fully developed drama.

Use of Odeons: In ancient Greece odeons were small, roofed theatres used for musical performances, poetry recitals, and political gatherings. Rhapsodes used odeons for their performances. Unlike the larger open-air theatres they were designed for indoor use. The most famous example of an odeon is the Odeon of Herodes Atticus in Athens, built in 161 AD on the south side of the Acropolis. Their design was influenced by the theatrons of large, open-air Greek theatres but adapted for indoor use. They were roofed to enhance acoustics; this was also a necessity in Bouleuterions. They had tiered seating similar to the theatres used for drama but in a smaller, more intimate layout.

Rhapsodes

Rhapsodes were professional performers who travelled from polis to polis, reciting epic poems to audiences. They were often accompanied by music, such as the lyre or aulos. Rhapsodes were highly skilled in the art of improvisation, and they would often add their own commentary and embellishments to the poems they performed.

In preliterate societies, poetry and song served a mnemonic purpose for the memorisation and recital of the legends and folktales of those societies for storytelling which had not been written down. The rhyme and rhythm of a poem or song make the words easier to remember and pass onto others. In pre-classical Greece, oral poetry was used to relate the tales from Greek myth ─ epic tales of olden-day heroes and their interactions with the gods.

These epic tales were preserved and retold by a professional class of bards or minstrels known as aoidoi or rhapsoidoi (rhapsodes or “song-stitchers”). The craft of the rhapsodes lay in their memory and knowledge of the vast corpus of Greek myth and legend. They had the ability to select and shape episodes from this corpus for public recitation. This oral poetry was typically sung or recited in the flowing rhythm of dactylic hexameter. In general Greek poetry did not use rhyme; the Ancient Greek language had too many natural rhythms for this to be considered beautiful.

At religious festivals throughout the Athenian year. Rhapsodes, the professional performers and singers of Homeric and other epics, sought an audience at the religious events where the crowds were so gathered. As with many Greek institutions competition was important. Rhapsodes formally competed against one another before groups of judges. The winner was awarded a prize. Such competitions may have been the origins of the competitions held at the Dionysian and Lenaean festivals for tragedy and comedy theatrical performances.

It was the rhapsodes who educated the Greek masses in their mythology,

Here are some of the more famous ancient Greek rhapsodes:

Demodocus of Rhodes, who was mentioned in Homer's Odyssey as a Rhapsode who performed at the court of Alcinous, king of the Phaeacians on Corfu.Epicharmus of Cos was a rhapsode and poet who lived in the 6th century BC.

Stesichorus of Himera was a rhapsode and poet who lived in the 7th and 6th centuries BC.

Arion of Lesbos, was a rhapsode and poet who lived in the 7th and 6th centuries BC.

Homer, the legendary author of the Iliad and the Odyssey.

It is possible to consider Thespis to have started by being an Aiodo for he travelled from place to place, performing before audiences, but the traditional story is that he was originally a choir boy who sang dithyrambs, which were songs about stories from mythology, for the public. Later he became known as the first actor and the inventor of tragedy in Ancient Greek theatre performance by stepping out of the Chorus line of the dithyrambic performance.

Rhapsodes and Ancient Greek Drama

It is very likely that Rhapsodes had a significant influence on the origin of Ancient Greek drama. Rhapsodes were professional performers of epic poetry, most famously the works of Homer like the Iliad and Odyssey. Their role in the oral tradition and public performance provided a foundation for the development of Greek theatrical practices in several ways:

Performance Techniques: Rhapsodes were skilled in recitation, often using expressive voice, gestures, and rhythm to engage audiences. These techniques likely influenced the dramatic styles employed in early Greek drama, particularly the use of actors and the chorus.

Storytelling and Myth: The content of rhapsodic performances, which centred on myths and heroic tales, formed the narrative core of much of Greek drama. Tragedies and comedies frequently drew from the same mythological corpus, reinterpreting the stories for theatrical presentations.

Choral Elements: The rhapsodic tradition also emphasised the communal and ritualistic aspects of performance. The chorus in Greek drama, which played a central role in early tragedies, might have evolved from similar collective narrative practices found in epic recitations.

Religious and Civic Context: Rhapsodic performances were often part of religious festivals, such as the Panathenaic Festival in Athens, which celebrated Athena. Similarly, Greek drama emerged in a religious context, particularly during festivals honoring Dionysus, like the City Dionysia. The overlap in ritualistic function suggests a continuity in the cultural use of performance.

Transition to Dialogue: While rhapsodes performed solo with an emphasis on narrative, Greek drama introduced dialogue between characters, often derived from interactions hinted at in epic poetry. This evolution from monologue to dialogue was a pivotal step towards fully developed drama.

Use of Odeons: In ancient Greece odeons were small, roofed theatres used for musical performances, poetry recitals, and political gatherings. Rhapsodes used odeons for their performances. Unlike the larger open-air theatres they were designed for indoor use. The most famous example of an odeon is the Odeon of Herodes Atticus in Athens, built in 161 AD on the south side of the Acropolis. Their design was influenced by the theatrons of large, open-air Greek theatres but adapted for indoor use. They were roofed to enhance acoustics; this was also a necessity in Bouleuterions. They had tiered seating similar to the theatres used for drama but in a smaller, more intimate layout.

References

Rhapsode - Wikipedia

Citharode - Wikipedia

Aulos - Wikipedia

Rhapsode - ancient Greek singer - Britannica

Homer - Wikipedia

Demodocus (Odyssey character) - Wikipedia

Arion - Wikipedia

Stesichorus - Wikipedia

Citharode - Wikipedia

Aulos - Wikipedia

Rhapsode - ancient Greek singer - Britannica

Homer - Wikipedia

Demodocus (Odyssey character) - Wikipedia

Arion - Wikipedia

Stesichorus - Wikipedia

Pindar - Wikipedia

Search results for Aoidoi in JSTOR

The Oxford Classical Dictionary : Ross, W. D. Ed.- Rhapsodes - Internet Archive

Ion (dialogue) - Wikipedia

The Internet Classics Archive - Ion by Plato

The Cambridge Companion to Greek Lyric - Google Books

Greek Rhetoric before Aristotle : Enos, Richard Leo - Internet Archive

The Concise Oxford Companion to Classical Literature: Howatson, M. C - Internet Archive

The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours : Nagy, Gregory - Internet Archive

A Companion to Ancient Epic - Google Books

A Companion to Ancient Epic - Internet Archive

Jonathan Ready; Christos Tsagalis (13 August 2018). Homer in Performance: Rhapsodes, Narrators, and Characters. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-1-4773-1603-0.

George Grote (1882). A History of Greece from the Earliest Period to the Close of the Generation Contemporary with Alexander the Great. Allison. pp. 135–.

Judith A. Hamera (2006). Opening Acts: Performance In/as Communication and Cultural Studies. SAGE. ISBN 978-1-4129-0558-9.

Tragedy and Epic by Ruth Scodel in a Companion to Tragedy - Wiley Online Library

Jonathan Ready; Christos Tsagalis (13 August 2018). Homer in Performance: Rhapsodes, Narrators, and Characters. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-1-4773-1603-0.

Dictionary of the Ancient Greek World

Rhapsodes at Festivals

Martin L. West

Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik

Bd. 173 (2010), pp. 1-13

Published by: Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH

https://www.jstor.org/stable/20756824

González, José M. 2013. The Epic Rhapsode and His Craft: Homeric Performance in a Diachronic Perspective. Hellenic Studies Series 47. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies.

http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_GonzalezJ.The_Epic_Rhapsode_and_his_Craft.2013.

10. The Rhapsode in Performance

13. Rhapsodic hypokrisis and Aristotelian lexis

Introduction: Toward an Understanding of Greek Poetic Contestation - Center for Hellenic Studies

Search results for Aoidoi in JSTOR

The Oxford Classical Dictionary : Ross, W. D. Ed.- Rhapsodes - Internet Archive

Ion (dialogue) - Wikipedia

The Internet Classics Archive - Ion by Plato

The Cambridge Companion to Greek Lyric - Google Books

Greek Rhetoric before Aristotle : Enos, Richard Leo - Internet Archive

The Concise Oxford Companion to Classical Literature: Howatson, M. C - Internet Archive

The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours : Nagy, Gregory - Internet Archive

A Companion to Ancient Epic - Google Books

A Companion to Ancient Epic - Internet Archive

Jonathan Ready; Christos Tsagalis (13 August 2018). Homer in Performance: Rhapsodes, Narrators, and Characters. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-1-4773-1603-0.

George Grote (1882). A History of Greece from the Earliest Period to the Close of the Generation Contemporary with Alexander the Great. Allison. pp. 135–.

Judith A. Hamera (2006). Opening Acts: Performance In/as Communication and Cultural Studies. SAGE. ISBN 978-1-4129-0558-9.

Tragedy and Epic by Ruth Scodel in a Companion to Tragedy - Wiley Online Library

Jonathan Ready; Christos Tsagalis (13 August 2018). Homer in Performance: Rhapsodes, Narrators, and Characters. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-1-4773-1603-0.

Dictionary of the Ancient Greek World

Rhapsodes at Festivals

Martin L. West

Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik

Bd. 173 (2010), pp. 1-13

Published by: Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH

https://www.jstor.org/stable/20756824

González, José M. 2013. The Epic Rhapsode and His Craft: Homeric Performance in a Diachronic Perspective. Hellenic Studies Series 47. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies.

http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_GonzalezJ.The_Epic_Rhapsode_and_his_Craft.2013.

10. The Rhapsode in Performance

13. Rhapsodic hypokrisis and Aristotelian lexis

Introduction: Toward an Understanding of Greek Poetic Contestation - Center for Hellenic Studies

No comments:

Post a Comment