Backstory

Ajax came to the Trojan from Salamis with twelve ships. He is an independent chief owing no allegiance other than to Agamemnon, the command-in-chief of the Achaian [Greek] forces.

Before the start of the play, Odysseus and Ajax have contended over who should receive the armour of the Greek warrior-hero Achilles who has been killed. The armour makes its wearer invincible and was specially made for Achilles by a god. Anyone who received this armoour would be recognised as the greatest warrior in the Greek army after Achilles. Trojan captives were asked to vote who had done the most damage to them during the Trojan War. And they voted that the armour should be awarded to Odysseus (they only came to this decision with the help of the goddess Athena). This enraged Ajax so much so that he vowed to assassinate the Greek commanders, Menelaus and Agamemnon, as they had disgraced him; he believed he was the greatest warrior aand deserved the armour more than Odysseus, but before he could get his revenge the goddess Athena has tricked him.

The Argument

Aias, the son of Telamon and Eribœa, was mighty among the heroes whom Agamemnon led against Troia, giant-like in stature and in strength; and in the pride of his heart he waxed haughty, and scorned the help of the Gods, and turned away from Pallas Athena when she would have protected him, and so provoked her wrath. Now when Achilles died, and it was proclaimed that his armour should be given to the bravest and best of all the host, Aias claimed them as being indeed the worthiest, and as having rescued the corpse of Achilles from shameful wrong. But the armour (so Athena willed) was given by the chief of the Hellenes not to him but to Odysseus, and, being very wroth thereat, he sought to slay the Atreidæ who had so wronged him, and would have so done, had not Athena darkened his eyes, and turned him against the flocks and herds of the host.

Dramatis Personae

Athena

Odysseus [warrior hero, commander of the defence of the right flank]

Ajax (Aias) [warrior hero, from Salamis. commander of the defence of the left flank]

Tecmessa [wife of Aias, Phrygian princess, Aias' captive concubine]

Teucros [half-brother of Aias]

Menelaos [King of Sparta, brother of Agamemnon, commander of the Spartan forces]

Agamemnon [King of Argos, supreme commander of the Achaean [allied Hellenic] forces in the war against Troy]

Eurysakes [son of Aias]

Attendant

Herald/Messenger

Chorus of Sailors from Salamis [Ajax's followers: these are warriors who both manned the ships and fought in the battles]

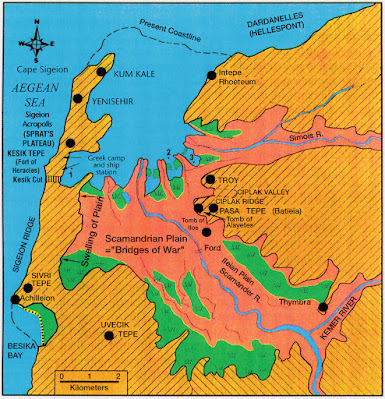

[Alternative description of setting: (1) At first, before the tent of Ajax, at the eastern end of the Greek camp, near Cape Rhoeteum on the northern coast of the Troad. (2) After line 814, a lonely place on the shore of the Hellespont, with underwood or bushes.]

Summary:

Enter the godess Athena Deus ex Machina on the roof of the skene [Theologeion]

Athena makes Odysseus invisible to Ajax as Odysseus is afraid to enter Ajax's tent. She tells him not to be afraid and to stand outside, and calls for Ajax.

Athena asks him whether he has killed the commanders of the army,

Ajax says he has, as they had robbed him of Achilles' armour, and now he's going to whip Laertes [Odysseus], whom he has chained up inside his tent as his prisoner, to death.

Athena asks Odysseus did he see all that.

Odysseus answers: "For I see well, nought else are we but mere phantoms, all we that live, mere fleeting shadows."

Athena disappears and Odysseus exits.

They complain that the booty, the sheep and the cattle, was also meant to be shared with them, and with all in the army.

Expecting Ajax, instead Tecmessa, Ajax's concubine, comes out of the tent.

She tells the Sailors that Ajax is greatly sickened with a storm of troubles. The Chorus ask her to tell them what has happened during the night in the tent. She confirms that Ajax has extremely violently killed many animals and is struck with a sickness [madness]. She is very sorrowful. The Chorus tell her they fear what might happen, that they and he might be done to death by order of the Commanders of the army, for he has killed the herds which they had captured from the enemy and the mounted soldiers guarding them. Tecmessa then desribes to them in great detail the mass slaughter of the animals inside the tent the previous night, cutting the heads off some, and hacking others. And how he had viciously whipped and especially cursed one which had been tied to the pole holding up the tent.

Ajax declares the Sailors to be his only true and faithful friends, and describes the slaughter surrounding him; he begs them to kill him. The Chorus refuse. Ajax describes what a mad fool he has been, and the shame of it. He tells the Sailors to go away out of his sight. The Chorus Leader tells him to calm down: what's done is now past. Ajax says Odysseus is the evil one, filthiest scoundrel in all the army and tool of all the mischief. The Chorus Leader tells Ajax his situation is desparate. Ajax appeals to Zeus to help him kill Odysseus and the two kings [Agamemnon and Menelaus], and then himself. Tecmessa begs to know why she should live after he is dead. Ajax begs the god of the Underworld to take him away: Athena has undone him. He will be killed by the army. The living and the land will no longer see him. He will lie abject in dishonour.

Ajax tells us that his name means Agony. He describes how many years previously his valorous father too had fought the Trojans with bravery and returned home with honour. But he will now bring shame upon the family, left as an outcast. Achilles would himself had given him his armour, but Menelaus and Agamemnon have contrived that a man with a dishonest mind should have them.

The Chorus contrast their harsh life in Troy with the happiness they enjoyed in their homeland, Salamis. Ajax's madness makes their wretched state worse. Ajax's mother and father will be greatly sorrowed when they hear the news of their son's action. They lament Ajax’s fate: better off to hide in Hades than to be a man plagued by such a disease [madness], for he is noblest of the war-tried, but is now wandering outside of himself with alien thoughts.

He is told that Ajax is not here.

Messenger bemoans that he has not come in a more timely fashion. Teucer instructed the messenger to tell Ajax not to go outdoors.

Chorus: But Ajax has gone out with good intentions.

Messenger: That was foolish. Teucer had told him it was important to keep him in his own tent. He would be safer. Today was only day when Athena would come to vex him with her anger. Indeed Ajax had told her in the midst of a battle when she was standing next to him, to go away and assist other Greeks. This invoked her hatred of him.

Tecmessa is called for.

Enter Tecmessa.

The Messenger tells her that if Ajax is not here, there is no hope for him. Teucer had given him strict instructions that he was to be kept in his tent and not go out alone. Calchas the seer and prophet had warned us.

Exit Tecmessa carrying Eurysaces, together with the Messenger

The Chorus splits into two groups exiting to both sides of the Orchestra.

The skene represents a bush by the seashore.

He tells the audience that it was the sword which Hector had given him [a gift, recognition from an enemy that he was a worthy and honourable foe].

Hector, of all friends

Most unloved, and most hateful to my sight.

Then it is planted in Troy's hostile soil,

New-sharpened on the iron-biting whet.

And heedfully have I planted it, that so

With a swift death it prove to me most kind.

He begs Zeus that Teucer be allowed to find his body first, to save his corpse from dishonour. He begs Hermes to conduct him down to the underworld quickly. He begs the Erinyes [the Furies] to come and sweep ruin upon the the Sons of Atreus, and wreak vengeance upon whole the army as well. And he requests Helios [the sun god] to rise up into the heavens in his chariot to relate the tale of his death to his parents. Finally, he begs Thanatos [the god of death] to attend him in the underworld.

He bids farewell to Salamis his dear home. and to Athens, and the streams and plains of Troy.

They say neither of the teams have found Ajax, neither in the east nor in the west.

3rd Kommos (A Lament) [Lines 879-973]

There is a cry from the bush. Tecmessa has found Ajax's body. She covers his corpse with a robe.

The Chorus alternate between speaking [the Chorus Leader] and singing, as does Tecmessa.

Enter Tecmessa

She laments. The Chorus join in with her lament.

4th Episode [Lines 974-1184]

The Chorus Leader comments: "Fine words! but don't shame the dead."

Chorus Leader: "I can't approve this, but the argument is strong."

Teucer: "Archery is an honourable art, not contemptible at all!"

Menelaus and Teucer now row with each other [stichomythia]: Teucer argues that was it not right that one's enemies had to lie dead and unburied on the field of battle? But was Ajax Menelaus' enemy? Teucer then claims that the votes obtained for the granting of Achilles' armour were fraudulent, and Menelaus was found out. Menelaus then said don't blame him, but those who judged it. Teucer accuses him of villainy. Menelaus: "This man must not be buried!". Teucer: "He will be buried at once!"

Menelaus describes Teucer's argument as reckless, and that he should calm down.

Teucer describes Menelaus' haughty foolishness, that a wise person has said that by outraging the dead you will live to regret it.

Menelaus exits saying he could use force.

Tecmessa and the child, Eurysaces, enter.

Exit Teucer

Teucer Re-enters. Tells everyone to get ready, Agamemnon is on his way.

Were these deeds not his!

Neither Agamemnon nor Teucer backs down.

Odysseus turns to Teucer and then tells him he will always be his friend and asks may he help in the funeral rites.

Exit Odysseus

References

Achaeans (Homer) - Wikipedia

Ajax the Great - Wikipedia

Ajax | Encyclopedia Mythica

Tecmessa - Wikipedia

ATHENA MYTHS 3 GENERAL - Greek Mythology - Theoi

(2013). Ajax (Aἴας). In The Encyclopedia of Greek Tragedy, H.M. Roisman (Ed.). doi:10.1002/9781118351222.wbegt0440

Ajax (Play) - Ancient History Encyclopedia

AJAX - SOPHOCLES | PLAY SUMMARY & ANALYSIS

www.ancient-literature.com › greece_sophocles_ajax

Ajax by Sophocles GreekMythology.com

A. S. “Jebb's Ajax.” The Classical Review, vol. 11, no. 2, 1897, pp. 113–116. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/692843.

Sophocles: The Plays and Fragments; with Critical Notes, Commentary, and Translation in English Prose by R.C. Jebb Pt 7 : Sophocles - Internet Archive

Jan Coenraad Kamerbeek (1953). The Plays of Sophocles: The Ajax. E. J. Brill.

H.D.F. Kitto (April 2011). Greek Tragedy. Chapter VI - The Philosophy of Sophocles: Taylor & Francis. pp. 123–. ISBN 978-1-136-80690-2.

Bernard M. W. Knox. “The Ajax of Sophocles.” Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, vol. 65, 1961, pp. 1–37. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/310832

Andreas Markantonatos (27 August 2012). Brill's Companion to Sophocles. J.P. Finglass - Ajax: BRILL. pp. 59–. ISBN 978-90-04-21762-1.

The Poetics of Greek Tragedy by Malcolm Heath - Internet Archive

J.P. Finglass (25 August 2011). Sophocles: Ajax. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-50465-2.

Lawrence, Stuart. “Ancient Ethics, the Heroic Code, and the Morality of Sophocles' Ajax.” Greece & Rome, vol. 52, no. 1, 2005, pp. 18–33. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3567855

Golder, Herbert. “Sophocles' ‘Ajax’: Beyond the Shadow of Time.” Arion: A Journal of Humanities and the Classics, vol. 1, no. 1, 1990, pp. 9–34. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20163444

Karakantza, Efimia D. “Polis Anatomy: Reflecting on Polis Structures in Sophoclean Tragedy.” Classics Ireland, vol. 18, 2011, pp. 21–51. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23621460

Hawthorne, Kevin. “The Rhetorical Resolution of Sophokles' ‘Aias.’” Mnemosyne, vol. 65, no. 3, 2012, pp. 387–400., www.jstor.org/stable/23253330

Simpson, Michael. “SOPHOCLES' AJAX: HIS MADNESS AND TRANSFORMATION.” Arethusa, vol. 2, no. 1, 1969, pp. 88–103. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/26307263

MARCH, JENNIFER R. “SOPHOCLES' ‘AJAX’: THE DEATH AND BURIAL OF A HERO.” Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies, no. 38, 1991, pp. 1–36. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43646729

Barker, Elton. “The Fall-out from Dissent: Hero and Audience in Sophocles' Ajax.” Greece & Rome, vol. 51, no. 1, 2004, pp. 1–20. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3567876

Stevens, P. T. “Ajax in the Trugrede.” The Classical Quarterly, vol. 36, no. 2, 1986, pp. 327–336. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/639277

Keyser, Paul T. “The Will and Last Testament of Ajax.” Illinois Classical Studies, no. 33-34, 2009, pp. 109–126. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/illiclasstud.33-34.0109

Tyler, James. “Sophocles' Ajax and Sophoclean Plot Construction.” The American Journal of Philology, vol. 95, no. 1, 1974, pp. 24–42. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/293816.

Henrichs, Albert. “The Tomb of Aias and the Prospect of Hero Cult in Sophokles.” Classical Antiquity, vol. 12, no. 2, 1993, pp. 165–180. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25010992.

Blume, Horst-Dieter. “THE STAGING OF SOPHOCLES' ‘AIAS.’” Mediterranean Archaeology, vol. 17, 2004, pp. 113–120. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24668143.

Kelly, Adrian. “AIAS IN ATHENS: THE WORLDS OF THE PLAY AND THE AUDIENCE.” Quaderni Urbinati Di Cultura Classica, vol. 111, no. 3, [Accademia Editoriale, Fabrizio Serra Editore], 2015, pp. 61–92, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24645173.

Clark, James T. "The Skene Door in the Prologue of Sophocles’ Ajax." Mnemosyne 72.5 (2018): 861-866. https://doi.org/10.1163/1568525X-12342669

SUPPLICATION AND HERO CULT IN SOPHOCLES’ AJAX by Peter Burian

Greek Versions

Sophocles, Ajax Perseus Digital Library

Teubner Edition - Ajax

Ajax - Sophocles - Google Books ed. P.J. Finglass, Cambridge Classical Texts and Commentaries

Translations

No comments:

Post a Comment