Iphigenia in Aulis or Iphigenia at Aulis (Ἰφιγένεια ἐν Αὐλίδι or Iphigenia Aulidensis) was written between 408 BC and 406 BC, and first produced a year later in 405 BC, posthumously by Euripides' younger son, as he himself had died a year earlier. Some scholars note later additions and amendments to the text of the play which has come down to us, text by other hands than his.

Argument/Hypothesis

When the hosts of Hellas were mustered at Aulis beside the narrow sea, with purpose to sail against Troy, they were hindered from departing thence by the wrath of Artemis, who suffered no favouring wind to blow. Then, when they enquired concerning this, Calchas the prophet proclaimed that the anger of the goddess would not be appeased save by the sacrifice of Iphigeneia, eldest daughter of Agamemnon, captain of the host. Now she abode yet with her mother in Mycenae; but the king wrote a lying letter to her mother, bidding her send their daughter to Aulis, there to be wedded to Achilles. All this did Odysseus devise, but Achilles knew nothing thereof. When the time drew near that she should come, Agamemnon repented him sorely. And herein is told how lie sought to undo the evil, and of the maiden's coming, and how Achilles essayed to save her, and how she willingly offered herself for Hellas' sake, and of the marvel that befell at the sacrifice.

Alternative Hypothesis

When the Greeks were detained at Aulis by stress of weather, Calchas declared that they would never reach Troy unless the daughter of Agamemnon, Iphigenia, was sacrificed to Artemis. Agamemnon sent for his daughter with this view, but repenting, he dispatched a messenger to prevent Clytæmnestra sending her. The messenger being intercepted by Menelaos, an altercation between the brother chieftains arose, during which Iphigenia, who had been tempted with the expectation of being wedded to Achilles, arrived with her mother. The latter, meeting with Achilles, discovered the deception, and Achilles swore to protect her. But Iphigenia, having determined to die nobly on behalf of the Greeks, was snatched away by the Goddess, and a stag substituted in her place. The Greeks were then enabled to set sail.

Dramatis Personae

Agamemnon – king of Mycenae [Argos], supreme commander of the Achaean [Greek] forces, husband of Clytemnestra, father of Iphigenia and Orestes, brother of Menelaus

Old Man – loyal slave of Clytemnestra and Agamemnon

Menelaos – king of Sparta , husband of Helen , brother of Agamemnon

Messenger 1 – attendant of Clytemnestra

Clytemnestra – daughter of Tyndareus, wife of Agamemnon

Iphigenia – teenage daughter of Clytemnestra and Agamemnon

Achilles – warrior hero, son of Thetis [a sea goddess] and Peleus, king of Phthia

Messenger 2

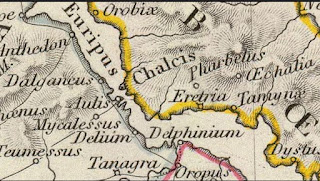

Chorus of Young Married Women from Chalcis, a city in Euboea just across the sea from Aulis. They have to sightsee of the vast Achaean [Greek] army and fleet that has mustered there at Aulis prior to its setting sail for the war on Troy.

Non-Speaking Parts

Clytemnestra's entourage

Orestes - the infant son of Clytemnestra and Agamemnon [a doll]

Achilles’ attendants and soldiers [Myrmidons]

Possible Distribution of Parts

Protagonist: Agamemnon and Achilles

Deuteragonist: Menelaus and Clytemnestra

Tritagonist: Old Man and Iphigenia

Setting: The camp of the Greek Army on the sea coast at Aulis. The Skene is Agamemnon's tent.

Summary:

Prologue [Lines 1-163]

Enter Agamemnon with letter writing tablets and an Old Man, faithful slave of Agamemnon. They chant their lines till Line 48.

Agamemnon is commander of the Greek forces, who have mustered at Aulis to sail against Troy. The Old Man is Agamemnon's and Clytemnestra's slave. Agamemnon tells the Old Man to come to him, but the Old Man is slow because of his age. There is a bright star in the sky near the Pleiades: Sirius, blazing bright but scarcely moving, no birds chirp and the winds have dropped, the sea is calm and silence prevails in the strait of Euripus. The ships are becalmed and cannot set sail for Troy [apoleia]. Agamemnon is pacing up and down agitated outside his tent. He is envious of the slave's life because he is free from danger, and lives in obscurity expecting no glory. Those in high renown have more worries. The Old Man says that those in high office have success.

Agamemnon explains that that success and high office is not everything that it is made out to be. True there is some sweetness in having high rank, but it brings pain to those who achieve it. This is the will of the gods.

The Old Man says that he does not admire leaders who think like this. Agamemnon must face adversity: what the gods will, will be. He directs our attention to the fact that Agamemnon is trying to compose a letter on a tablet, but is constantly erasing what he has written, and throwing the tablets down on the ground, breaking them. Agamemnon should discuss his problem with him, Tyndareus [Clytmenestra's father] had sent him as a loyal and trustworthy servant as part of Clytemnestra's bridal dowry, a long time ago.

Agamemnon relates the following background story: Leda had three daughters, including Helen and Clytemnestra. Helen was wooed by the best young men of Greece. So many came, but so much jealousy arose amongst them, with terrible threats, so much so that should any of them fail to win her hand, that Tyndareus, her father, decided to force each of the suitors to swear an oath to the effect that whoever won Helen as his wife, should she run away from that marriage with another, all of the rest of them would band together in an expedition, and by force of arms overthrow whether Greek or Barbarian, whoever had abducted her. She chose Menelaos for husband. He was Agamemnon's brother. Then Paris came from Troy to Sparta immediately afterwards, after he had made his famous Judgement of the three goddesses. There he fell in love with Helen and she with him. He took her off with him back to Troy. Then Menelaos invoked the promise that all of Helen's suitors had made on oath to Tyndareus. A call to war was made. The armed forces of the Hellenes (ships, shields, horses, chariots) had all gathered here at Aulis. Agamemnon was made commander-in-chief. ever since Agamemnon has cursed the day when he received this appointment.

The host of the Hellenes has found itself becalmed at Aulis. No winds blow: no ships can set sail. Calchas, the seer, has said that a sacrifice must be made to Artemis: Agamemnon must offer up his eldest daughter, Iphigenia, as a human sacrifice to the goddess. If Agamemnon does this Calchas has said that the winds will blow again.

Agamemnon then ordered Talythibius, his herald, to dismiss the army, for he could never consent to give up his daughter. Then Menelaos forced Agamenon to rescind this decree and made him agree to the sacrifice of Iphigenia. A plan was devised. A letter full of lies was sent to Clytemnestra telling her to bring Iphigenia to Aulis, where she would be married to Achilles; that if she didn't Achilles would refuse to go to Troy with the Greek army and return to his homeland at Phthia.

Agamemnon says that no one else knows about this plan except Calchas, Odysseus and Menelaos, all of whom have all been told. And now he says he has changed his mind once more. Then facing the audience and the Old Man he tells them that what they have observed him doing is removing the seal from a new letter and then re-sealing it, over and over, again. Finally he tells the Old Man to take this new letter back to Argos, and to give it to Clytemnestra. The new letter tells Clytemnestra says not now to bring Iphigenia to Aulis, but that her marriage to Achilles must await for another season.

Old Man: But Achilles may blow up in a huge rage because of this.

Agamemnon: Achilles is only lending his name to this scheme. He knows not what our real intention is.

Old Man: It is wrong of you, Agamenon, to offer your daughter to be the wife of this son of a goddess, and then only to bring her here to offer her up to another goddess in blood sacrifice for the Greeks.

Agamemnon: I know I am out of my mind, but hurry, Old Man, to Argos as fast as you can. Do not fall asleep by the wayside. If you do meet them coming on their way here, turn them around, sending them back to Argos.

Old Man: How will I prove my mission comes from you?

Agamemnon: Take this, my seal, with you.

Exit Old Man, setting off on his journey.

Agamemnon: No mortal man can ever hold onto success and luck for his whole life. If you have been born then so you shall suffer.

Exit Agamemnon

Parodos [Lines 164-302]

Enter the Chorus of Women from Chalcis

They chant an ode saying that they have crossed over the Straits of Euripus from Euboeia. They have come to see the huge army of the Achaeans led by Agamemnon and his brtoher Menelaos, and the thousand ships that have all gathered here at Aulis and which are about to set sail for Troy to bring back Helen. Paris of Troy had stolen her away from Sparta she who had been given to him by Aphrodite after having the judged her best in beauty against the jealous goddesses Athena and Hera.

The Chorus say they have climbed up, passing by a temple dedicated to Artemis, which overlooked the army of the Achaeans in the plain below. They list all the famous heroes they have seen there, including Ajax and Achilles, and their men, their tents, horses and arms.

Then they have counted and listed the commanders of the ships of the assembled armada, including the fifty ships of the Myrmidons from Phthia, Achilles' men; then the equal number of ships from the Argive, and the sixty ships from Attica; and the fifty ships of the Boeotians; and ships from Phocis, and an equal number from Locris; and the hundred ships from Mycenae; and more from Pylos and a dozen from Ainia, and ships from Elis and Taphia; Ajax has brought with him a dozen ships from Salamis. So powerful is the fleet which has been assembled here that no Asian [Trojan] fleet could ever hope or expect to win against them.

1st Episode [Lines 303-542]

Enter Menelaos holding the letter Agamenon has sent to Clytemnestra and the Old Man whom he has detained. They are standing outside of Agamemnon's tent. The Old Man says Menelaos has seized the letter from him and is to give it back. Menelaos had no right to take it from him. Menelaos says that the Old Man is merely a slave and that he had no business carrying such a letter whose content affects the whole of the Greek army. The Old Man says he will leave judgement of that to others. Menelaos refuses to give it back, telling the Old Man that he will bash his brains out with his mace. The Old Man says that would be a glorious death for his master.

Enter Agamemnon

The Old Man tells him: Look how Menelaos has taken this letter from me by force and is refusing to give it back. Menelaos says that he has a far greater right to be heard than the Old Man.

Exit Old Man

Agamemnon tells Menelaos to give back his letter to him. Menelaos tells him that he will not till he has shown it to the rest of the army.

Agamemnon: You broke the seal, so you now know what you had no right to know.

Menelaos: Yes, and now you will suffer for the evil which you secretly plotted.

Agamemnon: Where did you find it? Have you no shame?

Menelaos: I was watching out for the arrival of your daughter.

Agamemnon: Why are you spying on my affairs?

Menelaos: My own reasons. I am not one of your slaves.

Agamemnon: What? you won't let me rule in my own house!

Menelaos: No! Your mind is shifty: one thing yesterday, another different one today.

Agamemnon: Your smooth tongue frames wickedness neatly.

Menelaos: A disloyal heart is false to friends. I need to question you now. Do not turn your head away.

Menelaos explains how Agamemnon had been eager to lead the Greek army, appearing to be unambitious but in reality intent on commanding it. How he had been willing to listen to everyone no matter how lowly and allowing such persons to greet him personally by name. How he had used these tricks to gain advancement. Now that he has power he has turned his heart inside out; that he no longer loved his friends of yesterday: a good man holds on firmly to old friends. When he had come to Aulis with the army and fleet he became as nothing, confounded by a god-imposed fate, lacking favourable winds. The Danaans [The Greek forces] had urged him to abandon the cause, sending them and all the ships home. How bewildered he had looked when he heard this, when he realised he would never have the glory of captaining the thousand ships, nor of capturing Troy. And how Agamemnon had summoned Menelaos to the council of war, asking him what he could do to preserve his power and prevent fate from stripping him of his command.

Menelaos told him that Calchas, the prophet had said he must make a human sacrifice of his own daughter to the goddess, Artemis; that he had promised to slay his child on her altar; that he was eager to get this done; that he had sent a message to his wife to bring her here to Aulis on the pretence of being married to Achilles. But how he had now been found out changing his mind in secret. The heavens have heard that he would slay his daughter, but now they have also heard that he won't. Thousands struggle to gain power, but then fall away into ignominy.

Menelaos: O Greece, what sorrow I feel for you. Ready to perform a noble deed, she'll let the barbarians slip away, all because of you and your daughter. In an army, like in politics, noble blood doesn't make a leader. Any man with some sense can lead a city. The chieftain of an army must have a mind.

Chorus: When brothers quarrel it is terrible to watch the battle of their angry words.

Agamemnon: I will be sharp but also not so sharp with you, Menelaos. Such is noble. What I say to you is as a brother. Who has wronged you? what are you lusting for? a virtuous wife? You managed the one you had foolishly. Was that my fault? Must I pay the price for your misfortune? You're the one who's mad. You lost a bad wife, but then you threw the good fortune that the gods gave you all away when you wanted her back. And all the suitors who wanted to marry her who now obliged to fulfill the oath which Tyndareos had made them agree to. Take them! they're willing to fight your war. Go fight it with them. But as for me I will not kill my child: but your fortunes will not prosper by your vengeance on a worthless bed-partner whilst I suffer nights and days in tears having committed an unjust deed against a daughter of my own flesh and blood. If you don't wish to be sensible, I will spend the time putting my own affairs in order.

Chorus: This differs from what you said before, but it is good to hear you say you will spare your child.

Menelaos tells us that he is without friends. Agamemnon says he does if he stops trying to ruin their lives. He says he will be a true brother if he deals fairly with him and drop his malice. Menelaos accuses Agamemnon of not wanting to help his country in her need. Agamemnon then says that some god has struck both the country and Menelaos with lunacy.

Menelaos: Well then, betray you brother, and boast of your generalship. I have other friends. I will go to them. And I have other resources.

Enter a Messenger.

The Messenger tells Agamemnon that he has come with Clytemnestra who has brought his daughter, Iphigenia, and their baby son, Orestes, with her. He has rushed on ahead, leaving the ladies to bathe their feet in a cool fountain after their long journey. The horses have also been turned loose to feed in a meadow. The news of their arrival has spread amongst the whole army; thousands have rushed in curiosity to see them. The soldiers are asking questions: 'Does this mean a marriage? Is the king missing his daughter?' and some of them are also asking: 'Is there's going to be a marriage-sacrifice to Artemis, the godess who rules here at Aulis. And who is the bridegroom?' He has rushed on ahead to suggest making ready for the rites and sacrifices to Artemis, for the morrow at dawn will bring Iphigenia a day of blessing.

Agamemnon thanks the Messenger and tells him to go indoors.

Exit Messenger

Agamemnon bemoans the fate that has befallen him. How can he now dare to face Iphigenia? Some divine power has tricked him. An ordinary man might weep and tell his sorrows to the world. But what for a king? He must maintain his dignity. How can he now receive his wife? She must come to the wedding to fulfill her loving part. As for the maid Death will soon lie with her.

Agamemnon: I hear her begging "Father, why do you kill me? Is this my marriage? May you too have such a marriage, and all your friends as well! And baby Orestes, he will cry out meaningless words, but they will have clear meaning to me in my heart. O Paris, your love for Helen has destroyed my life! "

Chorus: As women from another city we too share your grief.

Agamemnon bemoans that he has lost. Menelaos has heard what Agamemnon has said. When he saw tears come to Agamemnon's eyes, he had a change of heart.

Menelaos: Brother, do not kill your child. My heart melts when I see your tears. Why should she die when Helen lives? That is not just or fair. What do I desire? I can always find another wife. Do I cast my brother aside just to possess Helen? I share kinship with Iphigenia. We are of the same blood, yet she is facing Death on the altar for the sake of my wife. Pity for the girl has swept over me for she would be killed on account of my marriage. What has Helen to do with this girl of yours? Disband the army. Let it leave Aulis. Stop your tears. The dire oracles concerning your daughter’s destiny, I want no part in them, after all we are brothers.

Agamemnon welcomes Menelaos' change of heart, saying he hates how brothers fall out over a woman or greed for an inheritance or a throne. And then he announces the following.

Agamemenon: But we have arrived at a fatal place. A compulsion absolute forces the slaughter of my child.

Menelaos asks why he has changed his mind. Agamemnon tells him that it is the assembled army which forces his hand. Menelaos tells him not to be afraid of the rabble and comments that Iphigenia could be slipped away back to Argos in secret. Agamemnon tells him that Calchas will publish the oracle to the army. Menelaos says that the seer can easily be done away with before he does that.

Agamemnon: The whole race of prophets are a damnable evil.

Menelaos: They are no good, good for nothing whilst they live.

Agamemnon says that there is another problem. Odysseus knows of the plan to sacrifice Iphigenia. And he loves popularity and is ambitious which makes him dangerous. He will stand up before the army and announce what Calchas' oracles had said and how he, Agamemnon, had promised to make this sacrifice to Artemis. Odysseus will whip up rage amongst the men and urge the sacrifice of Iphigenia. He will arouse and seize the soul of the whole army, who will come to kill Menelaos and himself. And even if he managed to escape home back to Argos they would follow him there and destroy the land.

Agamemnon: Such is the terrible circumstance in which I find myself. I am quite helpless: it's the will of the gods. Menelaus, go through the army and take all care that Clytemnestra learns nothing of this until after I have seized my child and sent her to her death, so that I may do this evil with the least tears.

Agamemnon orders the Chorus to keep his secret.

The ode also makes mention of how Paris had been a herdsman at Troy, playing melodies on his shepherd's pipe, and how the goddesses had summoned him to judge their beauty. That trial subsequently sent him forth to Greece to stand before an ivory throne and look into Helen's eyes where he had exchanged the ectasy of love with her. This was the origin of the quarrel between the Greeks and Trojans and led to the assault with ship and spear by the Greeks on Troy.

The Chorus cry hail to Iphigenia and Clytemnestra, welcoming them to Aulis. The Chorus does not reveal that they know what is going to happen to Iphigenia. They do not even suggest the worst of it.

Iphigenia [to Agamemnon] Father, it is a good and wonderful thing you have done, bringing me here!

Iphigenia: Oh? Before you were glad to see me, but now your eyes have no quiet in them.

Agamemnon [to Clytemnestra]: I am concerned about giving in marriage our daughter to Achilles! Such partings bring happiness, but the father must now give away his daughter to another home.

Clytemnestra: Have you perfomed the preliminary rites to the goddess?

Agamemnon: I am about to. That's what keeps us here.

Clytemnestra: And the wedding feast?

Agamemnon: After I have made the first sacrifices to the gods.

Clytemenestra: And the women's feast, where will that be held?

Agamemnon: Here, by the ships from Argos.

Clytemnestra: I hope all goes well. What must I do?

Agamemnon. You must obey me.

Clytemnestra: I always do.

Agamemnon: I will look after the wedding here, where the bridegroom is. You must return home to Argos to look after our other little daughters.

Clytemnestra: Who will raise the torch?

Agamemnon: I will attend to that tradition.

Clytemnestra: That doesn't seem right. Matters such as this are important.

Agamemnon: It is not safe for you to remain in a crowded camp.

Clytemnestra: It is right for a mother to give away her daughter,

Agamemnon: And the little girls ought not to be left alone at home.

Clytemnestra: The home is well guarded. They are perfectly safe.

Agamemnon: You must obey me!

Clytemnestra: No! By Hera, I rule the household. You manage war and politics.

Exit Clytemnestra into the tent.

Agamemnon says he has now made a complete mess of things. He wants his wife out of the way. He tells lies to his daughter and concocts plots. He says he has to consult Calchas what he must do to appease the goddess Artemis, and not bring disaster down upon Greece. A man must have wife who obeys him and knows her duty, or have rid of her.

2nd Stasimon [Lines 751-800]

The Chorus chant that soon the Greek forces will set sail for Troy, where Cassandra will fling her hair wildly as Apollo breathes into the power of prophecy.

The Trojans will stand on the battlements and towers of their city when the Greeks arrive with their forces. When Ares comes desiring to seize Helen from Priam's palace to bring her back to Greece by toil of battle.

Ares will besiege Pergamon, Phrygia's town, and in bloody battle will drag headless bodies away. Helen will soon learn what it is to abandon a husband. The wives of Lydia and Phrygia will see what fate awaits them, who will drag them away from their looms by their hair too as their homes burn around them, all because of Helen, daughter of Leda and Zeus, (if the tale can be trusted, or is it just an imagined myth?)

3rd Episode [Lines 801-1035]

Enter Achilles

He is looking for Agamemnon, the commander in chief. His men, the Myrmidons, are getting restless, nagging at him all the time. He wants to know how much longer it will be before the army sets sail for Troy. There's something supernatural in the manner how men joined this expedition.

Enter Clytemnestra

Clytemnestra welcomes Achilles and tells him who she is, and that it is appropriate he should come and hold her hand as he is about to be married to Agamemnon's and her daughter. Achilles knows nothing of this. He has never sought the hand of their daughter, nor has anyone told him about this. Both Clytemnestra and Achilles are surprised by what they have told each other. Clytemnestra says she has been deceived by a fictional wedding. Achilles says someone is laughing at them both.

He makes to enter Agamemnon's tent.The Old Man comes out and blocks his way.

The Old Man recognises who Achilles is and says he is the faithful slave of Clytemnestra and Agamemnon. He has something to say to them both, to Achilles and Clytemnestra, and that it is urgent; that Agamemnon plans to kill Iphigenia; that he will cut her throat with his sword. Clytemnestra says she thinks the slave is mad. Why does Agamemnon want to do this? The Old Man says that Calchas has declared this to be some god's will if the Greeks are to sail for Troy, to fetch Menelaos' wife, Helen, back: Agamemnon has to sacrifice his daughter to Artemis. He invented the marriage to Achilles as a pretext of bringing her to Aulis. The sacrifice of Iphigenia is the price of getting Helen back from Troy for Menelaos.

Clytemnestra bursts into tears. She asks the Old Man how does he know all this. The Old Man tells her that he was bringing a second letter from Agamemnon to her cancelling his first command to bring Iphigenia to Aulis, but Menelaos had seized it from him. Clytemenstra then turns to Achilles to ask him did he hear all this. Yes he has, and he can't ignore the deceit and insult that Agamemnon has played on him. This is an outrage to both of them. Clytemnestra falls on her knees begging Achilles to rescue her and Iphigenia.

Achilles agrees to help her. Normally he would obey the orders of the generals of the army, but not in this instance, because what Agamemnon proposes to do is evil and that he intends to show that he is a free man both here and at Troy. He will protect Clytemnestra, and as Iphigenia is "betrothed" to him so he will protect her from her father's knife. If anyone tries to rob him of her daughter before he goes to Troy he will stain his sword with their blood. If he does not do this the whole camp will call him a coward. He swears that Agamemnon will not lay a finger on her dress. Calchas, too, will be sorry if he is present with his barley meal and holy water at the sacrifice. Such men utter lies and will vanish in smoke. He will do all this and Iphigenia does not have to marry him, adding that he is pursued all the time by women.

King Agamemnon has insulted him, by his not asking for his consent to the plan he has treated him with contempt. This is unforgivable.

Clytemnestra asks whether Achilles would like her daughter to come out and clasp his knees in supplication. Achilles says that she does not have to, that the enterprise is his to rid them of these evils. He swears may he die if he does not save the girl's life. Achilles tells Clytemnestra that he will first try to persuade Agamemnon to act in a more sane manner. Clytemnestra praises Achilles for his unfailing friendship.

Clytemnestra tells Achilles that at heart Agamemnon is a coward. He is afraid of the power of the army. Achilles says that powerful arguments will defeat his. Clytemnestra asks what can she do? Achilles says she must kneel in supplication before him begging him not to kill his child. If he resists this she must come to Achilles. If she succeeds in changing his mind, Achilles need not be involved and the army won't accuse him; he will have won the argument by reason and not force. Everything will turn out well for both Clytemnestra and Iphigenia,

If Clytemnestra should fail Achilles says he will be on the watch for her in the right place. She is not to rush through the soldiers' camp as that might bring disgrace down upon the family. Agamemnon is highly thought of throughout Greece.

Achilles exits to the side.

Clytemnestra declares him to be an upright man.

Exit Clytemnestra into Agamemnon's tent.

3rd Stasimon [Lines 1036-1097]

The Chorus sing a joyful ode about the wedding-chorus which led the feasting and dancing at the marriage of Peleus to Thetis [Achilles' father and mother]. How the wine flowed at their celebration together with the dancing of the fifty daughters of Nereus [Thetis' sisters] honouring the marriage rites.

How the Centaurs came riding in announcing that Thetis will bear a son [Achilles], the glory of all Thessaly: Cheiron has prophesied this, one skilled in Apollo's arts. They predict that he, the son, will lead the Myrmidons to destroy the city of Priam [Troy]. Achilles will be clad in the golden armour that Hephaetus wrought. O happy and glorious day.

But Iphigenia's wedding day will be different. A garland will be placed on her head by the soldiers from Argos, the same that would be put on the head of a heifer which had been dragged for sacrifice on an altar. In this case there will be no heifer, only a girl raised to be the bride to an Argive prince. Where is the goodness and virtue in this? Ruthless disregard holds power. Men forget they are mortal. Goodness is trodden down. Lawlessness overrules the law. The terror of the gods no longer unites mankind when this is the reward of wickedness.

Exodos [Lines 1098 - 1531]

Clytemnestra complains Agamemnon has been a long time absent from his tent. Iphigenia is in tears having heard what her father has plotted for her, sacrifice of her life.

Clytemnestra: Why look! here comes that wicked monster, Agamemnon.

Agamemnon: I have things to say while Iphigenia is indoors, things which a young bride ought not to hear. The girl must come with me so send her out. Everything is ready: lustral waters for purification, barley to sprinkle on the sacrificial fire. And heifers are ready to fall before the marriage rites, yielding up their blood, soon to flow for Artemis.

Clytemnestra: These things sound fair to me, but as for your real intention, such words seem to say nothing good about that.

Exit Agamemnon

Enter Achilles

Iphigenia's Speech

Mother, listen to me. We must thank Achilles for his zeal. You are angry with your husband. This is foolish. I understand how difficult it is to stand against an irrestible force, and the doom it might bring hard to bear. Let us praise our friend but we must make sure he is not blamed by the army for any of this. Such a thing would only bring utter ruin down upon him and win us nothing. I am resolved to die and want to die well, with glory. shunning whatever is weak and ignoble. All of Greece is turning its eyes upon me, and only me. All lies in my hands. Through me the fleet will set sail, and will be able to capture and overthrow Troy. Through me barbarians will no longer be able to ravish Greek women, and drag them away from happiness and their homes. Paris will be made to pay the price for his rape of Helen. All this can be brought about by my death. I will win honour as the saviour of Greece and my name will be blessed as the one who set Greece free.

It is wrong for me to love life too much. Mother, you gave birth to me for all of Greece, not just yourself. Our country has suffered wrong and injury. Thousands of men have armed themselves. Thousands more sail in these ships. With great daring they will face the enemy and die for Greece. Will my life prevent this and prove to be the obstacle against their resolve? Where is the justice in this? To the soldiers who are going to die what can we say?

Consider this further. Is it right for one man to make war upon all the Greeks for the sake of one women and surely die? Far better that ten thousand women die to keep this one man alive.

Mother, if Artemis truly wishes to take the life from my body, who am I, a mere mortal, to oppose the divine will? That is unthinkable. I dedicate my body to Greece. Sacrifice me: capture and plunder Troy, my glorious monument. Greek were born to rule barbarians, and not otherwise. They are slaves by nature, and we have freedom in our blood.

Chorus: Princess, your nature indeed is noble and true, but the fault lies with the goddess and fate.

Achilles' Speech

Exit Iphigenia taken away by guards

Exit Chorus

Supplementary [Alternative] Ending to Iphigenia at Aulis [Lines 1532 - 1630]

This ending has been transmitted as an alternative and additional ending of the play. Modern scholars think it is probably spurious and of a later date. Its function seems to be that it seeks to justify and provide continuity for the story described in the myth of Iphigenia in Tauris, in which Iphigenia has been rescued by the goddess Artemis from being slaughtered on her altar at Aulis.

[The Chorus has remained in the Orchestra]

Enter a Second Messenger has come from the Temple of Artemis, and has witnessed the sacrifice of Iphigenia. He asks Clytemnestra to step outside. He has news of the wonders he had beheld there.

Clytemnestra steps out of Agamemnon's tent. She asks the messenger to tell her his account of what he saw.

The Second Messenger tells her that after they had reached Artemis' sacred grove with Iphigenia, the Greek army was assembled. When Agamemnon saw his daughter walk up to the grove, he wept.

Iphigenia stood before her father and said "Father, I am here at your command. Willingly I give my body to be sacrificed for Greece. If it is the will of heaven lead me to the goddess' altar. May you all prosper and win victory in this war, and return home safely. Let no Argive touch me with his hand. I offer my neck to the knife." Every man present spoke of the maid's courage and nobility.

Talthybius then proclaimed an order for the army to keep silent. Calchas, the seer and priest, usheathed his sharp knife putting it in a golden vessel. He placed a wreathe on the Iphigenia's head. Achilles took up the barley and the purified waters, and ran round the altar crying out to the goddess Artemis to accept this their sacrifice, pleading for the fleet to be allowed to set sail, and for a blessing from her for a safe voyage to Troy and for the Greek army to destroy Troy.

All heads were bowed. Calchas took up the knife, uttered a prayer, looking for a place on the maid's neck where to strike his blow. Suddenly a great miracle came to pass. Everyone heard Calchas' blow strike, but no one understood or could explain what happened afterwards. The maid had vanished as if by magic. In her place there lay a hind panting its last: the goddess' altar was covered in its blood. Calchas spoke: "Commanders, you see this victim, a mountain hind. Artemis has received this sacrifice with joy in lieu of the maid, and has accepted the offering. She grants safe voyage to the fleet to sail for Troy. Let every sailor make his way to his ship, for on this day the fleet must leave Aulis and cross the Aegean." After this the deer's body was placed on the temple's furnace. When the holy flames of the furnace had finished consuming it, Calchas delivered a prayer for the safe homecoming of the army.

The messenger explained to Clytemnestra that he had been sent to her by Agamemnon to give her a report of all this. By what has happened he has won immortal glory throughout Greece. He tells her that their daughter has clearly ascended into the heavens to be with the gods, and that she should put aside her grief. The gods act in ways which men do not expect. They save those dearest to them, for she who has died has come alive again.

Chorus: With gladness we hear this messenger's report.

Clytemnestra: O child! what god has stolen you from me? How may I know that this is not a false story made to stop my grieving?

Chorus: King Agamemnon approaches. He will tell you the same story.

Enter Agamemnon from the side.

Agamemnon: My wife, we can now be truly happy. Our daughter is now in the company of the gods. Now you must take baby Orestes home. The army has to make the voyage. It will be a long while before I return home from Troy to be able to greet you again. Farewell and may all go well with you.

Exit Agamemnon

Chorus: Go with good fortune to the land of the Phrygians. May you capture fine spoils from Troy.

Exeunt Clytemnestra and the Chorus.

References

Iphigenia in Aulis - Wikipedia

Iphigenia in Aulis by Euripides - GreekMythology.com

Euripides: Iphigenia at Aulis - Tom's Learning Notes

Iphigenia - GreekMythology.com

Calchas - Wikipedia

Calchas - GreekMythology.com

Euripides: Iphigenia at Aulis (Ἰϕιγένεια ἐν Aὐλίδι) - Wiley Online Library

IPHIGENIA AT AULIS - EURIPIDES | PLAY SUMMARY & ANALYSIS | Sacrifice of Iphigenia

Iphigenia in Aulis - Course Hero

The Story of Iphigenia in Greek Mythology - Owlcation - Education

Calchas - GreekMythology.com

Achilles (The Trojan War Hero) - GreekMythology.com

Menelaus - GreeekMythology.com

Agamemnon - GreekMythology.com

Talthybius - Wikipedia

Clytemnestra - GreekMythology.com

Artemis (Greek Goddess of the Hunt and the Moon) - GreekMythology.com

Helen - GreekMythology.com

Orestes - GreekMythology.com

Judgement of Paris - Wikipedia

Electra - GreekMythology.com

Aulis (ancient Greece) - Wikipedia

Frederick Apthorp Paley. Euripides: With an English Commentary. Volume 3: Containing Hercules Furens, Phoenissae, Orestes, Iphigenia in Tauris, Iphigenia in Aulide, and Cyclops. Cambridge Library Collection. Academia Renascens. Independently Published. ISBN 978-1-68941-996-3.

Euripides with an English commentary - Internet Archive

Hulton, A. O. “Euripides and the Iphigenia Legend.” Mnemosyne, vol. 15, no. 4, 1962, pp. 364–368. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4428688.

Lush, Brian V. “POPULAR AUTHORITY IN EURIPIDES' ‘IPHIGENIA IN AULIS.’” The American Journal of Philology, vol. 136, no. 2, 2015, pp. 207–242., www.jstor.org/stable/24562757.

Herbert Siegel. “Agamemnon in Euripides' 'Iphigenia at Aulis'.” Hermes, vol. 109, no. 3, 1981, pp. 257–265. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4476212.

Sorum, Christina Elliott. “Myth, Choice, and Meaning in Euripides' Iphigenia at Aulis.” The American Journal of Philology, vol. 113, no. 4, 1992, pp. 527–542. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/295538.

McDonald, Marianne. “Iphigenia's ‘Philia’: Motivation in Euripides ‘Iphigenia at Aulis.’” Quaderni Urbinati Di Cultura Classica, vol. 34, no. 1, 1990, pp. 69–84. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20547029.

Weiss, Naomi A. “The Antiphonal Ending Of Euripides’ Iphigenia in Aulis (1475–1532).” Classical Philology, vol. 109, no. 2, 2014, pp. 119–129. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/675252.

Pietruczuk, Katarzyna. “The Prologue of ‘Iphigenia Aulidensis’ Reconsidered.” Mnemosyne, vol. 65, no. 4/5, 2012, pp. 565–583., www.jstor.org/stable/41725240

Burgess, Dana L. “Lies and Convictions at Aulis.” Hermes, vol. 132, no. 1, 2004, pp. 37–55. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/4477582

Walsh, George B. “Iphigenia in Aulis: Third Stasimon.” Classical Philology, vol. 69, no. 4, 1974, pp. 241–248. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/267779.

“The Iphigenia in Aulis.” Ritual Irony: Poetry and Sacrifice in Euripides, by Helene P. Foley, Cornell University Press, ITHACA; LONDON, 1985, pp. 65–105. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctvn1tb8f.6

Hollinshead, Mary B. “Against Iphigeneia's Adyton in Three Mainland Temples.” American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 89, no. 3, 1985, pp. 419–440. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/504358

Laura K. McClure (17 January 2017). A Companion to Euripides. Chapter 20 by Isabelle Torrance -Iphigenia at Aulis: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 284–. ISBN 978-1-119-25750-9.

Andy Hinds (3 May 2017). Iphigenia in Aulis. Oberon Books. ISBN 978-1-78682-136-2.

Sean Alexander Gurd (5 July 2018). Iphigenias at Aulis: Textual Multiplicity, Radical Philology. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-2538-8.

Christopher Collard; James Morwood (24 March 2017). Euripides: Iphigenia at Aulis. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1-80034-580-5.

Lawrence, S. (1988). Iphigenia at Aulis: Characterization and Psychology in Euripides. Ramus, 17(2), 91-109. doi:10.1017/S0048671X00003118 http://bit.ly/3brR1nu

Willink, C. W. “The Prologue of Iphigenia at Aulis.” The Classical Quarterly, vol. 21, no. 2, 1971, pp. 343–364. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/637787.

George Kovacs PhD. Thesis IPHIGENIA AT AULIS: MYTH, PERFORMANCE, AND RECEPTION

Mousike and Mythos: The Role of Choral Performance in Later Euripidean Tragedy NA Weiss - 2014 - escholarship.org. Chapter 4 Iphigenia in Aulis p.134-

Euripidean drama : myth, theme and structure : Conacher, D. J - Internet Archive p. 249-

David Kovacs (2003). Euripidea Tertia. Iphigenia Aulidensis: BRILL. pp. 138–. ISBN 90-04-12977-4.

Dissimilar Representations of Agamemnon in Ancient Greek Literature

E Bellwoar - 2015 - Pennsylvania State University

https://honors.libraries.psu.edu/files/final_submissions/3033

Ritual and Communication in the Graeco-Roman World - Greek Sanctuaries as Places of Communication through Rituals: An Archaeological Perspective - Presses universitaires de Liège

Iphigenias at Aulis : textual multiplicity, radical philology Sean Gurd (2005)

Greek Versions

Teubner - Euripides - Iphigenia Aulidensis

Euripides, Iphigenia in Aulis - Perseus Digital Library

Ιφιγένεια εν Αυλίδι by Euripides - Project Gutenberg

Iphigeneia at Aulis C.E.S. Headlam

Euripides with an English commentary F.A.Paley - Internet Archive p.480

Iphigenia at Aulis - Euripides - Google Books Aris & Phillips Classical Textx

Readings in renaissance women's drama : criticism, history, and performance, 1594-1998 - Internet Archive

3. Jane Lumley's Iphigenia at Aulis pp 129-41

Translations

Euripides IV : Euripides p. 209 Internet Archive - University of Chicago PressEuripides, Iphigenia in Aulis - Perseus Digital Library

Iphigenia At Aulis by Euripides - Internet Classics Archive

Iphigenia in Aulis (Euripides) - Wikisource

Iphigenia At Aulis translated by E. P. Coleridge

Euripides - Arthur S. Way

Iphigenia in Aulis (Buckley) - Wikisource

Bacchae ; Iphigenia at Aulis ; Rhesus : Euripides - Internet Archive David Kovacs p. 155-

Iphigenia among the Taurians ; Bacchae ; Iphigenia at Aulis ; Rhesus : Euripides - Internet Archive p.84-

Orestes, and other plays : Euripides - Internet Archive P. Vellacott p. 363-427

Euripides (19 April 2013). David Grene, (ed.). Euripides V: Bacchae, Iphigenia in Aulis, The Cyclops, Rhesus. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-30898-2.

Euripides (2017). Iphigenia at Aulis. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-911226-46-8.

Euripides (17 May 2012). Euripides: Iphigeneia at Aulis. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-60116-1.

Three tragedies by renaissance women - Internet Archive

The Tragedie of Iphigenia in a version by Lady Jane Lumley (ca 1555)

Iphigenia at Aulis : Euripides - Internet Archive

Audio/Visual

Iphigenia w/eng subs - YouTube - Michael Cacoyannis (1962)

Iphigenia in Aulis, Euripides - Reading Greek Tragedy Online - YouTube - Center for Hellenic Studies

Ancient Greek theater performance: Iphigenia in Avlidi of Euripides - YouTube

Iphigenia : Audio Archive : Internet Archive

No comments:

Post a Comment